Mineral exploration increasingly operates at the intersection of geology and data, where analytical methods must be applied with a clear understanding of both their potential — and their limits. For McLean Trott, Ph.D., P.Geo, this balance has developed through two decades of work across the day-to-day realities of exploration, from field-based geology to data-driven analysis.

Trained as an economic geologist, McLean has worked in the mineral exploration space since completing a bachelor’s degree in geology at Brandon University in 2005. His early career took him across Canada, Mexico, Peru, and Chile, where he focused on field-based porphyry copper exploration. Much of this work involved hands-on geological mapping and sampling, along with drill-core logging in active exploration settings. In Peru, he also designed and led large geochemical soil sampling programs around the Haquira porphyry and nearby prospective claim blocks in the high Andes of the Apurímac region within the Eocene–Oligocene (Andahuaylas–Yauri) belt.

Beginning in 2020, consulting roles expanded McLean’s exposure to additional deposit styles and introduced him to a wider range of analytical approaches. As his responsibilities evolved, his work shifted toward data analysis and desktop-based interpretation, alongside greater involvement in training and mentoring. This transition included periods working as a geochemist and, more recently, a specialization in geodatascience, culminating in the completion of a Ph.D. at Queen’s University in 2024.

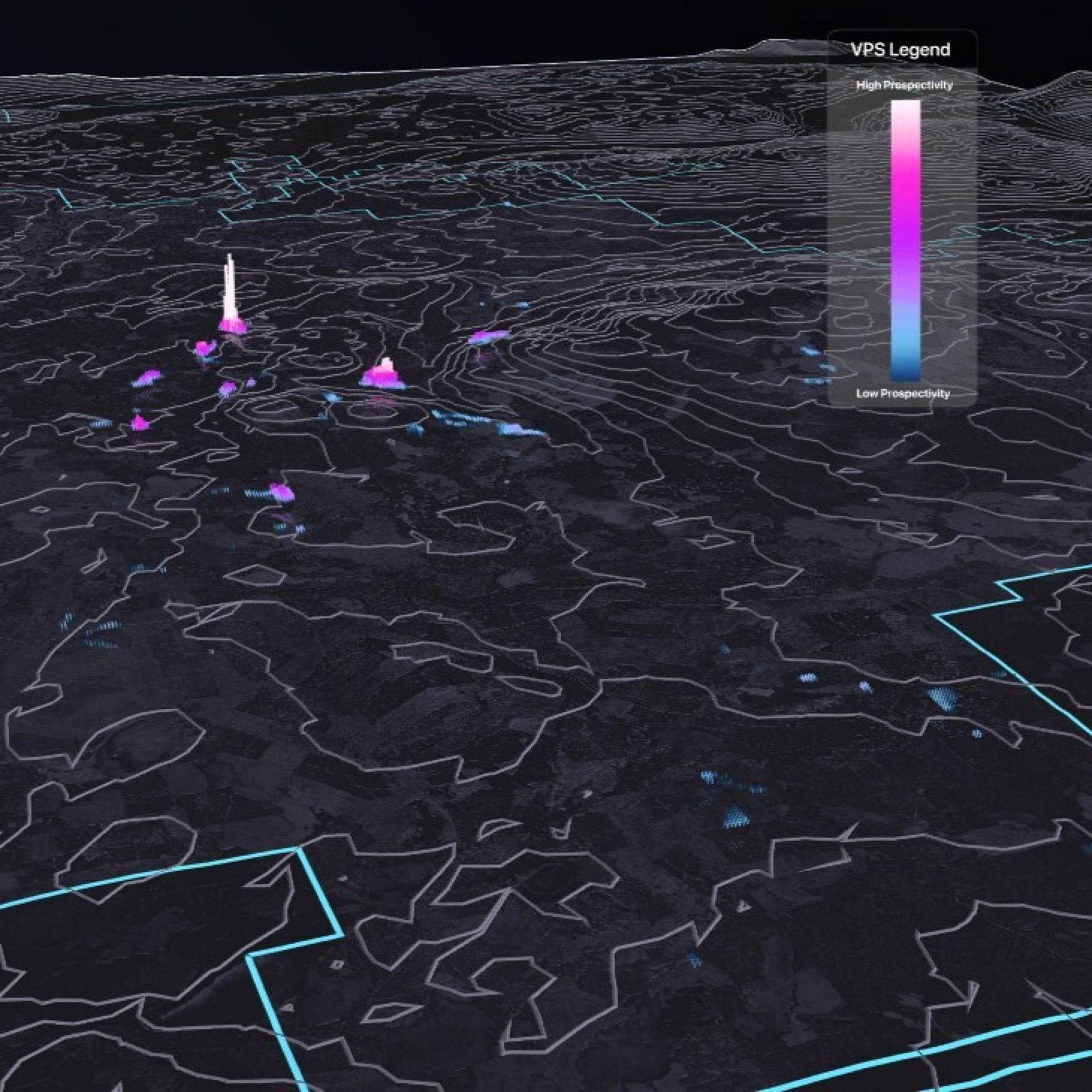

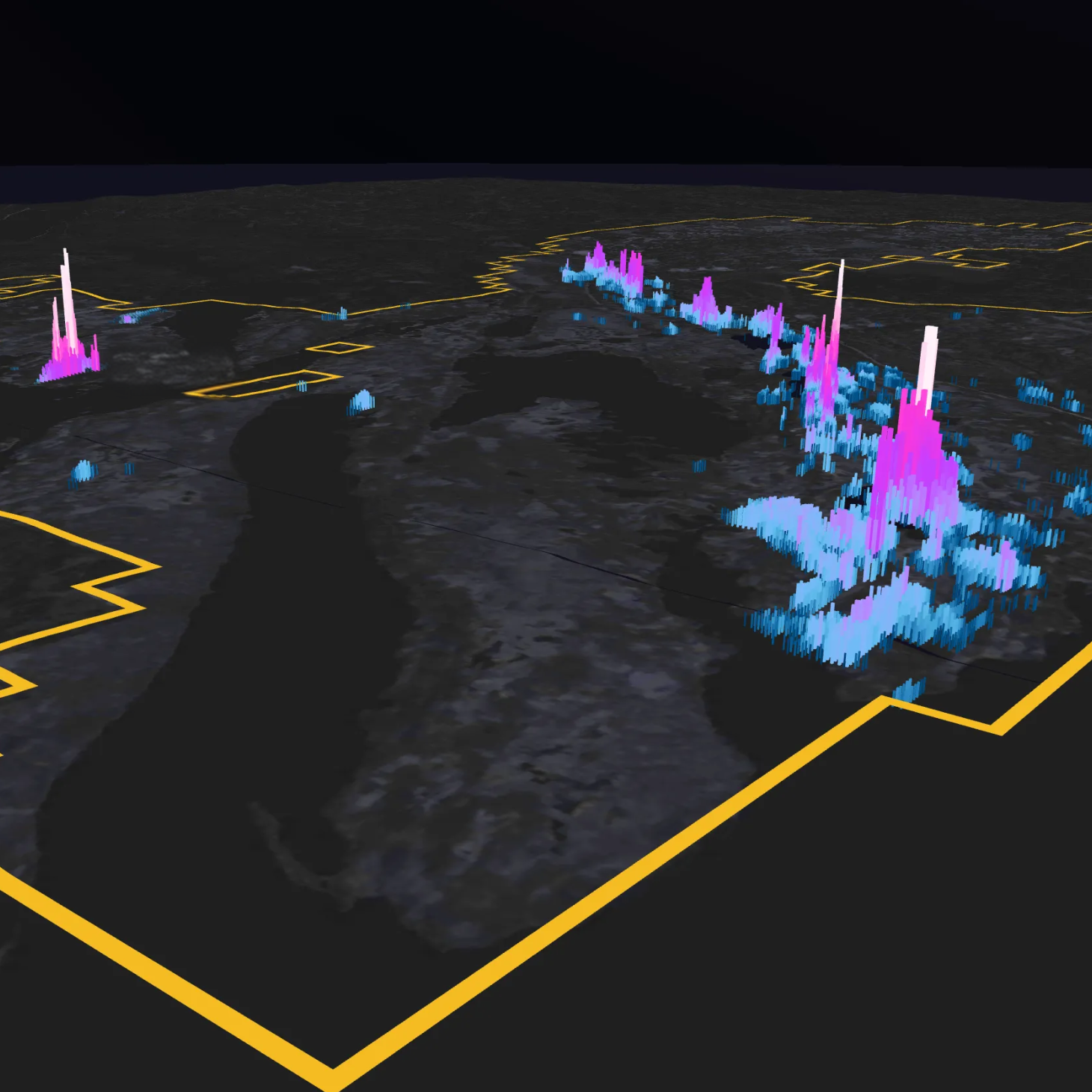

As Principal Geoscientist at VRIFY, McLean now works with internal and external stakeholders to ensure that predictive exploration models within AI prospectivity mapping software DORA — part of the VRIFY Predict product suite — begin as fit-for-purpose exercises and mature through iterations, remaining grounded in geological context.

In this conversation, McLean discusses why data analytics and AI have become necessary additions to the exploration toolkit, and how misunderstanding uncertainty can impede their value in exploration decisions.

1. What motivated you to join a tech company building AI software for the mining and exploration industry?

McLean Trott: Data analytics is a natural addition to the exploration and discovery toolkit. As an industry, we’re collecting better and more data than ever before. At times, human cognition is the limiting factor, rather than access to data. So AI tools can be immensely helpful in practice to ingest and understand this data. Parallel to this, we need to find more deposits with fewer geologists than at any previous time. The resource requirements for the energy transition are substantial.

A lot of experienced geologists are retiring, universities are shuttering geoscience programs, and the young professionals who do complete geoscience degrees are rarely choosing economic geology as a career path.

Putting these factors together, I think the biggest contribution I can make to the future is to help get enabling technology, like AI prospectivity tools, into the hands of explorers. VRIFY is where I knew I could do this using the VRIFY Predict suite.

2. From working closely with clients at VRIFY, what do you think is most commonly misunderstood about data or uncertainty?

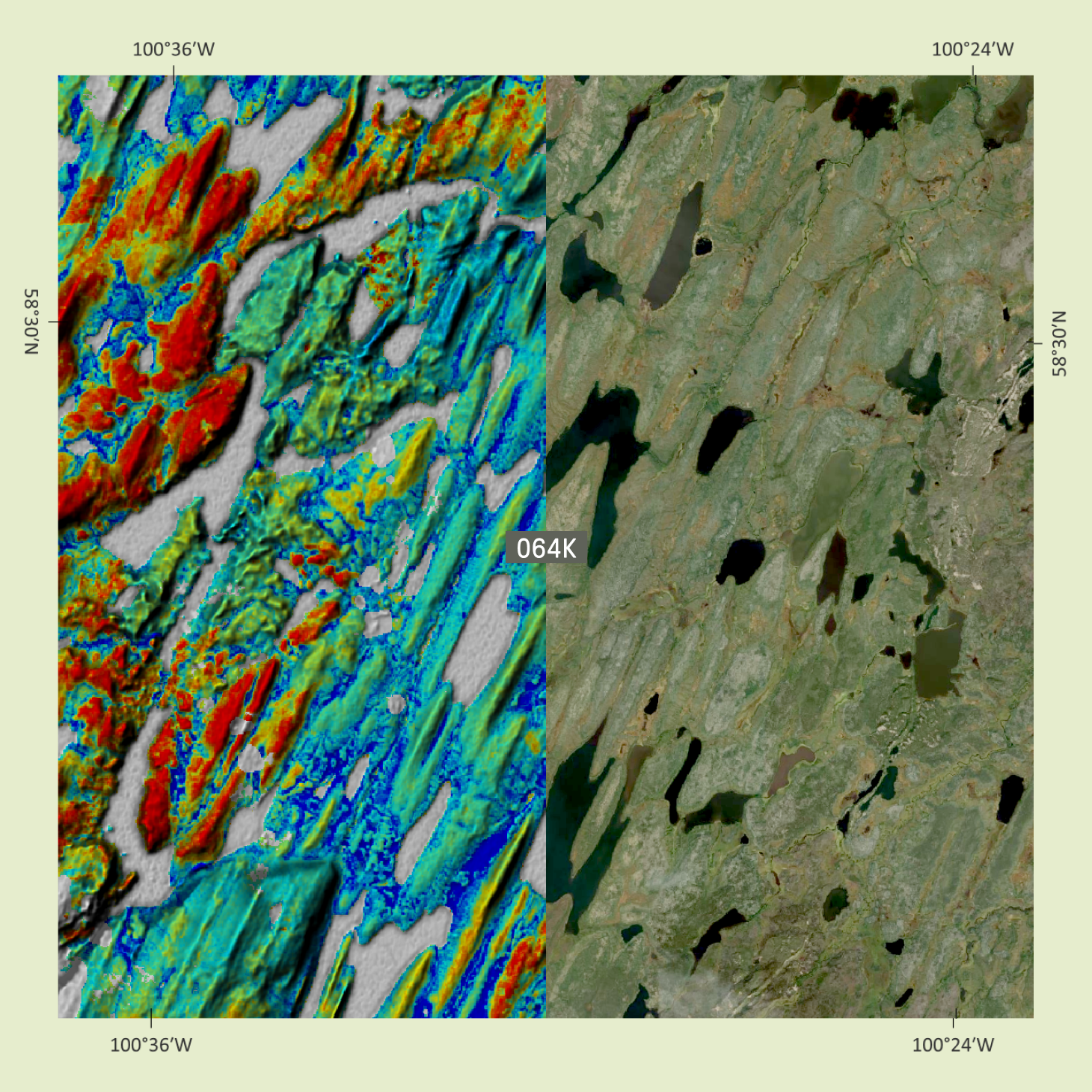

MT: The most misunderstood aspects of this sort of work relate to outcomes. The outcome of a predictive workflow is a probability map that shows how similar rock properties at each location are to the training data. This similarity is specific to the input layers and can be explained in different ways. An area that is very similar to the training area is not necessarily similar because it is also mineralized.

This means there is often a need for a very direct conversation about the limitations of a prospectivity map. AI outputs still require human interpretation to be used effectively. They need to be considered alongside local geology and site knowledge, and applied to inform targeting rather than replace geological reasoning. Ideally, AI-driven outcomes should stimulate more geological thinking and decision-making, not less. So it’s important to guide users toward that understanding.

3. From what you’ve seen, what tends to limit the usefulness of analytical or AI outputs for exploration teams?

MT: In a lot of cases, lack of experience in data analytics or AI can get in the way of applications. Like any other tool, it’s best used when the user understands its strengths and weaknesses.

Let’s look at this with a carpentry analogy.

A hundred years ago, houses were built with hammers and nails, hand saws, a plumb bob, and a few other manually operated tools. Every house builder in Canada today still has all of these tools and uses them on the job site every day. But they also now use a nail gun for putting shingles on the roof, a mitre saw for quickly and consistently cutting boards, a laser level for leveling the frame, and digital design tools like AutoCAD for planning and laying out the structure.

None of these tools would be enough to build a house on their own. But used together and properly, they allow a house to be built in a fraction of the time it would take using manual tools alone. Like building a house, finding an economic ore deposit requires using a variety of tools in the right way and at the right time. Just as houses were built before laser levels existed, ore deposits were found before AI tools existed. But maybe we can find them just a bit faster and a bit more systematically by using AI tools in addition to the tried-and-tested methods, in the right way and at the right time.

4. What misconceptions do you most often encounter about AI in mining and mineral exploration?

MT: Probably the most common misconception that can appear around AI is the “silver bullet” fallacy. This idea that all of our problems can be solved by AI (not just in exploration and mining) is counter-productive; it sets users up for disappointment. Most of this can be dispelled with exposure and education.

I think historically this has probably been true of many technologies in the mineral exploration space. They begin life as something new and interesting, where one camp might believe that “tech X” is going to revolutionize everything (the optimists, those who believe in silver bullets), another camp might reject “tech X” entirely (the cynics or skeptics), and an initially small camp is curious enough about “tech X” to understand its scope and limits and how it fits into the bigger picture. These are the pragmatists, who ultimately are perceived as innovators — not because they are inherently innovative, but because they are persistent enough to take the time to understand a new technology holistically and apply it appropriately. It’s these pragmatists that develop, implement, and improve technology through time and persistence. You could substitute “electrical geophysics,” “UAVs,” or “AI” for “tech X,” and this would still apply.

To return to education, it is through education that the optimist and cynic camps shrink as they move into the pragmatist camp, and new technology gets implemented as it should. It’s not a silver bullet, but another tool in the toolkit that improves outcomes when applied alongside established methods.

5. How do you see geoscience and AI evolving over the next several years, and what changes would you like to see in the exploration and mining industry to support that evolution?

MT: Agentic workflows are likely to become more ubiquitous and lead to a simplification of geoscience (and all) software. Agents are currently pretty basic and frequently flawed, but they’ll get better. Necessarily, we’ll see more data stored with better rigour to enable these agentic workflows. Emphasis on quality assurance and quality control across all data types and curated databases, both private and public, will take on more importance.

More broadly, I would like to see a fundamental structural change in the way exploration is carried out. By this, I mean a shift away from short-term thinking and strategy. Junior explorers are closely tied to the ups-and-downs of the stock market. Major companies too; commodity price fluctuations or leadership changes can translate into massive shifts in focus and priorities. The upshot of this dynamism is that projects and people move around regularly. Teams are built, restructured, and shifted. Projects are acquired, sold, abandoned. As a result, the continuity of exploration is regularly broken, and data and knowledge are lost in the process. Good projects get delayed, and bad projects consume unnecessary bandwidth.

From a bird’s-eye perspective, new funding models with long-term horizons are needed. It should be more feasible to maintain a team and focus on a good project with a long enough runway to get to production decisions. This is a massive challenge. It means a runway of something like two commodity cycles, at a minimum.

Long-term, non-partisan funding from federal or provincial/state sources might be a solution. Support from well-funded industries that rely on stable metal supply chains might help. Programs where major producers provide support to junior explorers, like BHP’s Xplor program, might become more commonplace and provide agile juniors with much-needed support and resources.

In the meantime, while these changes are on their way, the industry can take easy steps to mitigate the damage from this volatility. Companies of all sizes can ensure that they acquire, evaluate, and warehouse their data rigorously, rather than relying on Excel spreadsheets or USB thumb drives. They can support public institutions like universities and geological surveys that act as objective repositories for knowledge about a deposit or terrane. In short, find ways to ensure that data, and the knowledge arising from that data, can persist in the long run.

<hr />

It’s clear that McLean believes that progress in exploration depends on continuity over time and on how well data and knowledge are carried forward. In his view, AI emerges here not as a replacement for geological judgement, but as a tool meant to inform exploration decisions without supplanting human reasoning, and a motivator for improvements in data hygiene and curation. This perspective is reflected in DORA and the broader VRIFY Predict suite, which help geoscientists make better decisions from increasingly large and complex datasets.

<hr />

To learn how VRIFY applies AI-assisted analysis to support data-driven exploration decisions, explore DORA or connect with our Geoscience Team.

.png)

.png)

.png)

.png)