A career grounded in fundamental science has shaped how Julien Mailloux, M.Sc., Director of Research & Development, approaches the application of AI in mineral exploration at VRIFY. His academic training began in chemistry, then progressed from physics to geological engineering, with economic geology providing a bridge between physical principles and Earth systems. This trajectory culminated in an M.Sc. in economic geology and geochemistry at the University of Toronto, examining hydrothermally enriched nickel–copper magmatic deposits. Alongside this geoscience skillset, Julien pursued formal training in AI and data science through a postgraduate program and a MicroMasters, situating his work at the intersection of mathematics, machine learning, and applied geoscience.

This cross-disciplinary perspective has been reinforced through extensive field-based experience. Earlier in his career, Julien managed and contributed to exploration programs in Nunavik, Eeyou Istchee James Bay, and the Abitibi region in Quebec, ranging from early-stage regional exploration to deposit definition and mine-site settings. His fieldwork addressed a wide spectrum of deposit types, including volcanogenic massive sulphide systems, orogenic gold, platinoid-rich magmatic deposits, and several atypical gold occurrences. Through projects with junior explorers as well as mid-tier and major mining companies, he gained exposure to much of the mine lifecycle, connecting grassroots exploration and early production environments with later analytical work informed by practical exploration realities.

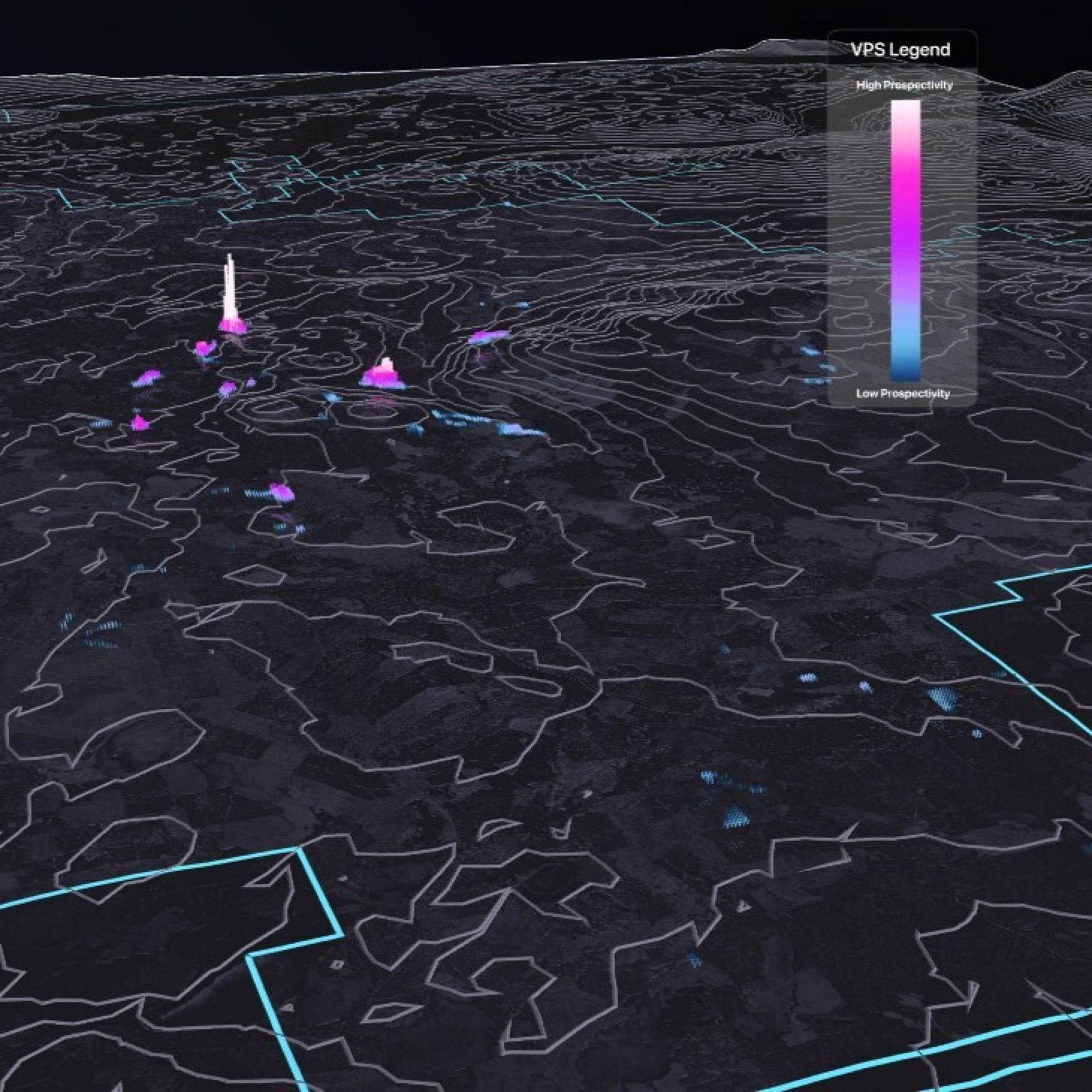

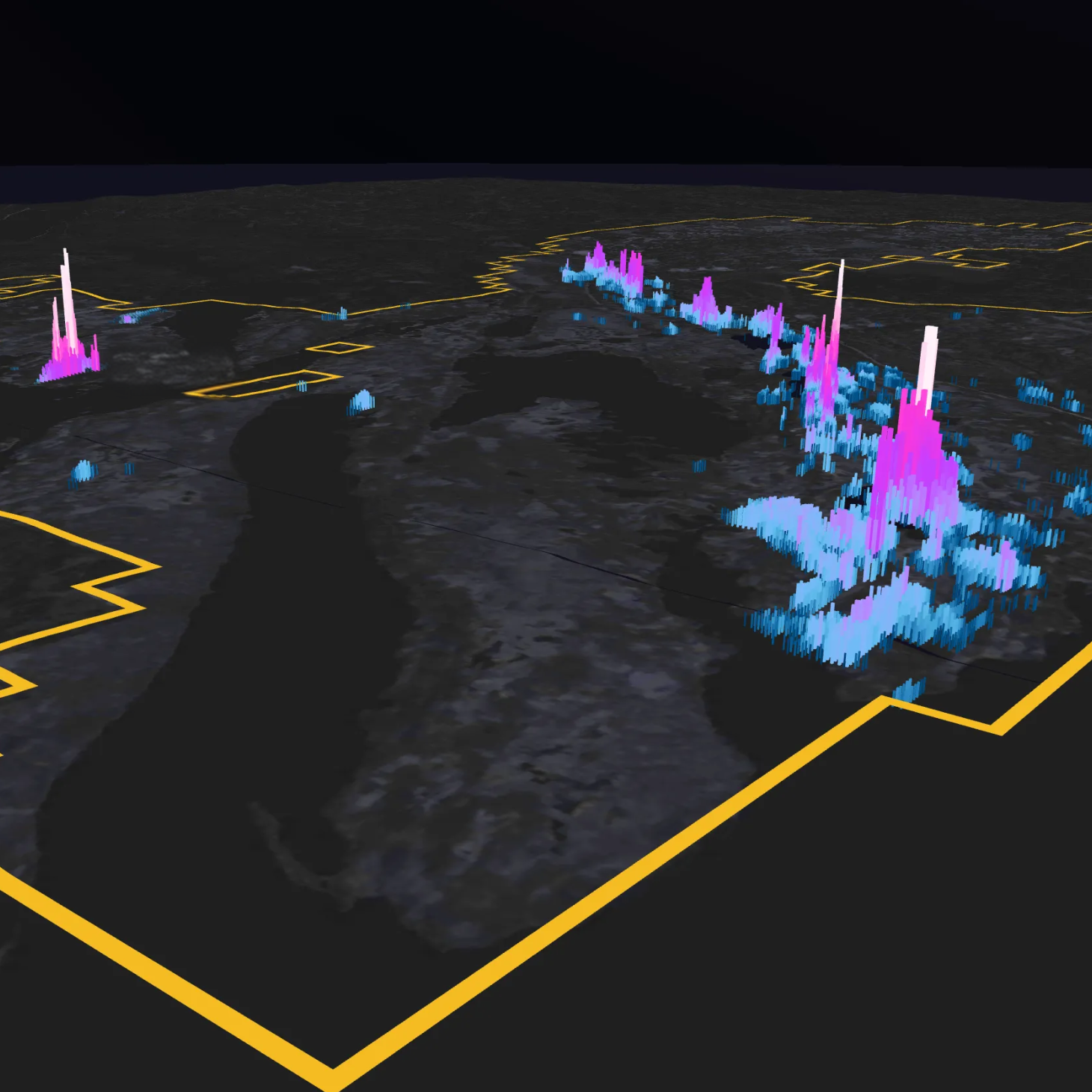

At VRIFY, Julien leads the company’s AI function, drawing on fundamental scientific training in geoscience and quantitative analysis to develop data science tools for the mining industry. His work spans the development of AI infrastructure and the productionalization of machine-learning systems across VRIFY Predict, a suite of Exploration Intelligence software, including AI prospectivity mapping software DORA. Beyond exploration, his mandate extends across the mining value chain, with a longer-term focus on building scalable AI capabilities and establishing the organizational mechanisms required to deploy these tools effectively.

In this conversation, Julien reflects on why mining remains uniquely positioned for AI-driven change, and on how interpretive constraints around data and uncertainty influence the application of geoscience knowledge as new analytical approaches emerge.

1. What motivated you to move from geoscience analytics and consulting to a tech company building AI software for the mining and exploration industry?

Julien Mailloux: The challenge of materially disrupting an industry. Mining is one of the few sectors rich in high-quality, multi-modal measurements that still are not being fully leveraged. It is also an industry with a profound and lasting impact on humanity; many of our most pressing needs rely on minerals.

AI is well-suited to the constraints of mineral exploration: abundant data, significant investment requirements, high-risk endeavours, and increasingly modest returns on investment.

2. Since joining VRIFY, what has surprised you most about how exploration teams actually work with data?

JM: A few things. Clients often believe that barren samples have little value for creating models. In reality, both barren and mineralized samples are important, because the model learns a decision boundary between mineralized and non-mineralized signals. To build a robust decision system, the model needs both.

Clients also often have very nascent data governance when it comes to curating datasets. Many believe that Excel sheets are sufficient and that it is not worth investing in a proper system to manage their data. However, acquiring these datasets represents a large share of exploration spend, and future value is strongly constrained by the quality and context of the information and the insights the data can reveal. Taking the time to curate and store data properly is a trivial expense compared to drilling, sampling, and quality assurance and quality control with assay labs, yet it is data curation that unlocks a property for AI products.

This is why we have been focusing on applying data engineering best practices from other industries to better unlock the value of exploration data.

3. From working closely with clients, what do you think is most commonly misunderstood about data or uncertainty?

JM: I often notice a tension between interpolation and extrapolation. As both a geoscientist and a physicist, I have seen geologists approach mineral exploration through the lens of mineral systems, looking for characteristics documented in the literature from known occurrences. This is fundamentally interpolation: using established knowledge to identify targets that resemble what we’ve seen before, streamlining exploration by targeting and confirming mineralization based on familiar patterns, whether at continental scale or deposit scale.

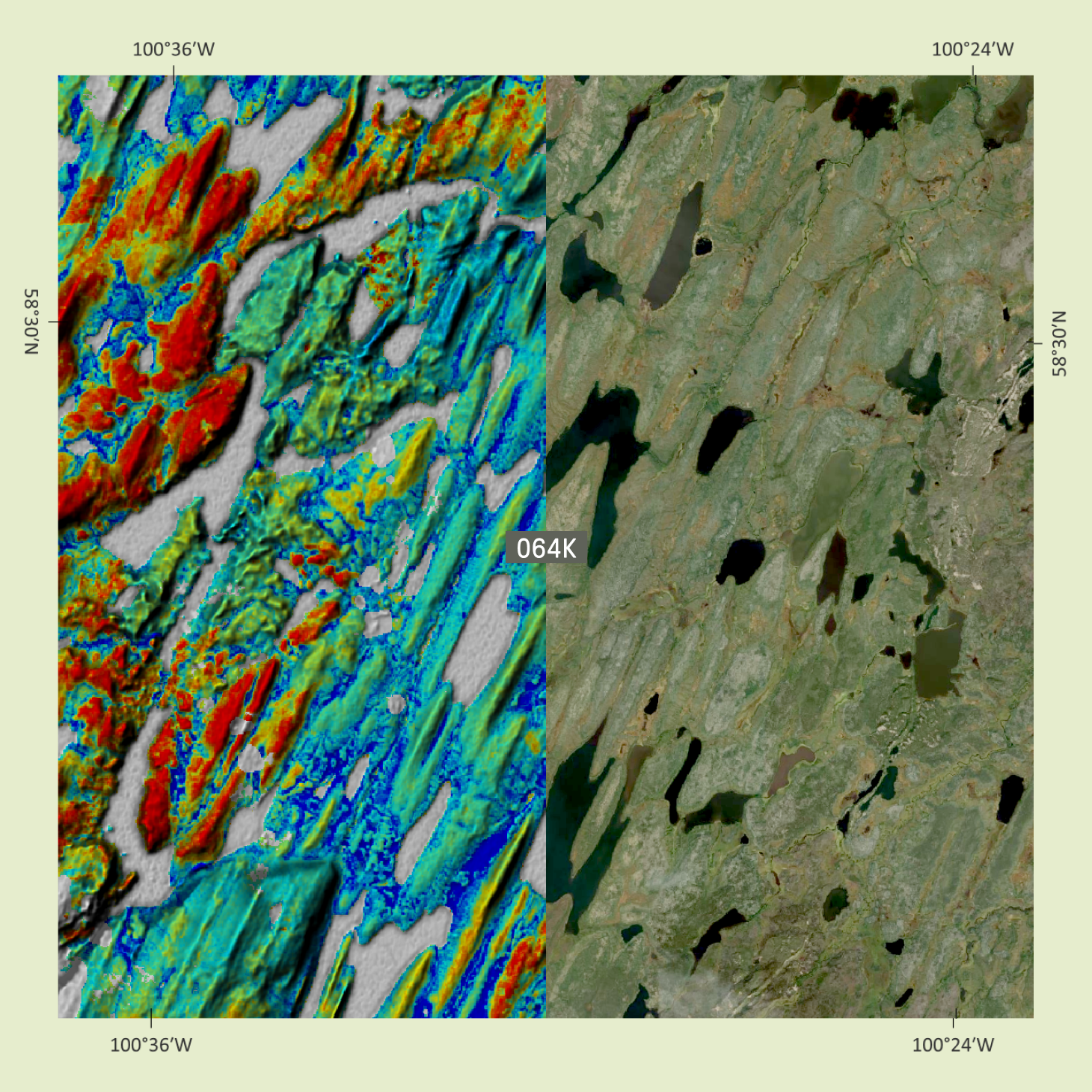

By contrast, state-of-the-art neural networks take a connectionist approach, finding patterns across large volumes of data through data-driven optimization. These models learn internal representations that can yield accurate predictions, but they typically do not explain the decision process. Critically, AI, like VRIFY’s DORA, can surface non-obvious relationships, sometimes highlighting prospective areas that do not fit neatly into established mineral-system frameworks, because the signal is not obvious to humans or sits outside our usual estimations.

Confirmation bias is powerful here. Mineral explorers often prefer predictions that confirm what they already believe, similar to how they interpret geochemical surveys, geophysics, or sampling campaigns. They trust interpolated results because these align with their mental models. One of the strengths of AI, however, is that it can synthesize large volumes of data without human confirmation bias and propose insights beyond the familiar.

As a result, I used to hear that “the model doesn’t work” when predictions do not align with expectations, and teams may disregard targets that don’t match their mental model without ever testing them. Yet exploring these unconventional areas, even through low-cost surface exploration, often reveal opportunities that a reliance on interpolation and confirmation bias would otherwise cause us to miss.

4. Do you have any predictions for geoscience or AI trends we’ll see in 2026 and over the next three to five years?

JM: I expect 2026 to be the year of agentic AI, an orchestration paradigm where large language or multimodal models plan and execute tasks using knowledge, tools, and, in some cases, multiple cooperating agents to achieve goals. In 2025, this approach materially accelerated software development. In 2026, we’ll likely see it applied more broadly beyond software engineering. It is well-suited to semi-automating repetitive, high-friction tasks that can be debilitating for knowledge workers.

Looking at the next three to five years, I anticipate three main developments:

(1) Physics-informed neural networks (PINNs) become increasingly important. In traditional machine learning and generative AI, models learn by minimizing the difference between predictions and ground truth through optimization of a loss function. But geoscience is governed by physicochemical processes operating within geological systems, such as deformation under tectonic stress, volcanism, and hydrothermal alteration. These processes are constrained by chemical and physical laws. In PINNs, you incorporate those constraints into training to better ground predictions, keeping them truer to the science behind mineral deposits.

(2) Work on digital twins will enable mining “world models.” These models would maintain a grounded representation of a mine or mineral processing plant, receive goals to achieve, and generate sequences of actions to fulfill those goals. This unlocks applications such as autonomous robotics and mine production workflow optimization.

(3) Development and adoption of Kolmogorov–Arnold Networks (KANs) increases as potential alternatives to multi-layer perceptrons (MLPs) where interpretability matters. With current architectures, neural networks often behave like black boxes; we can’t directly understand why a model made a given prediction and must rely on post-hoc explanation methods. KANs, in contrast, use learnable univariate functions on edges, which can be more directly visualized and sometimes distilled into human-interpretable relationships. This makes them promising, though it remains an active research area.

5. How do you see geoscience methodologies and AI converging in the future?

JM: Neuro-symbolic AI, which combines data-driven learning with formal representations of domain knowledge, will become an important avenue for geoscience applications. The current mainstream approach in AI is deep learning: a connectionist paradigm where models learn patterns via optimization with no predefined rules. This can be powerful, but it often lacks transparent reasoning.

Mineral exploration, however, is built on decades of observation and laboratory work. Geophysics to characterize deposits, geochemical analysis to define rock types, microanalysis to map and understand deposit genesis, and models of geological environments and sequences of events that allow deposits to form. From these studies, we have developed a wealth of frameworks describing mineral systems, yet we struggle to operationalize that knowledge at scale without adding bias.

Neuro-symbolic approaches merge both paradigms by combining neural networks’ probabilistic pattern recognition with formal logic and knowledge representation. This mirrors how geologists work: identifying a mineral system from a set of characteristics and then executing an exploration strategy from distal to proximal signatures until they hit the orebody. In other words, it incorporates both data and domain knowledge to guide the model.

<hr />

For Julien, the promise of AI in mineral exploration lies not in replacing established geoscience frameworks, but in extending them beyond the limits imposed by human bias. When rigorous data practices are combined with analytical methods capable of operating at scale, exploration teams can test assumptions more systematically and identify signals that would otherwise remain obscured. This perspective underpins how VRIFY continues to develop and refine AI-driven tools, including DORA and the broader VRIFY Predict product suite, for mineral exploration.

<hr />

To learn how VRIFY applies AI-assisted analysis to support data-driven exploration decisions, explore DORA or connect with our Geoscience Team.

.png)

.png)

.png)

.png)