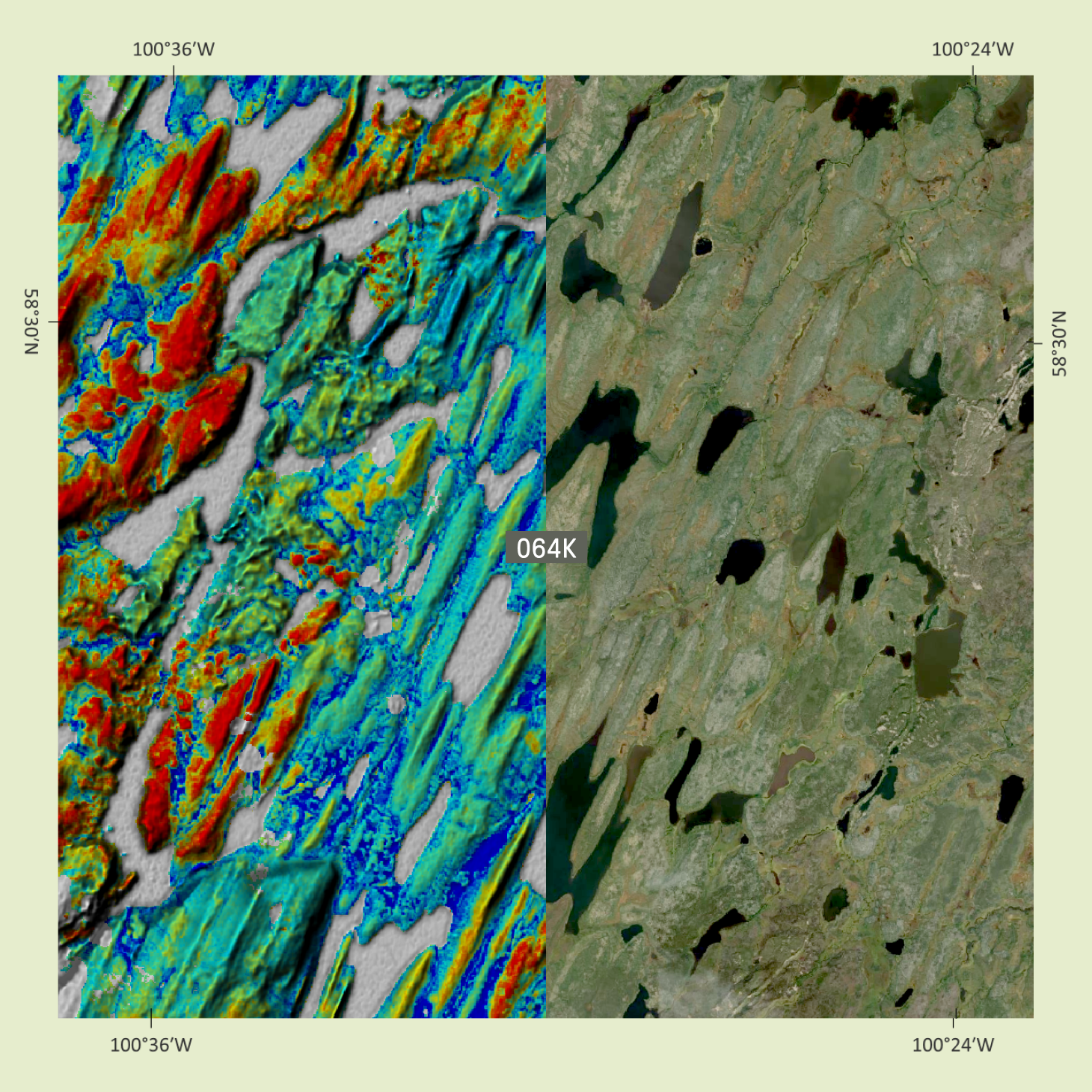

Machine learning (ML) is reshaping mineral exploration by enabling faster, more comprehensive analysis. The expansion of computational and cloud frameworks, combined with increasingly sophisticated learning architectures, has changed what can be drawn from geological information. Models can now integrate diverse sources of evidence simultaneously, revealing relationships that conventional interpretation may overlook. This progress is advancing how geologists test hypotheses and evaluate targets. Yet the strength of any result still depends on the foundation beneath it: dependable, coherent data. Algorithms cannot compensate for weak inputs.

The Condition of Exploration Data

Across the industry, the information underpinning exploration remains uneven. Data from drilling, assays,1 mapping, geophysical surveys,2 and field observations is frequently recorded in incompatible formats and at different resolutions, with accompanying metadata that is incomplete or missing, which complicates consistent interpretation. These characteristics vary widely, not only between organizations but also within individual projects through time. Historical archives add further complexity when context is lost or measurement systems are inconsistent. An example of this can be seen in Assessment Report3 search returns for drilling and geochemistry in the Iron Mask region of southern British Columbia, Canada.

These factors combine to create a dataset that is extensive in volume but fragile in structure. Even subtle inconsistencies and duplications can compound through analysis — much like how mismatched or repeated entries in electronic medical records can affect clinical decision support4 — until the underlying geological patterns are no longer clear. For ML, which relies on internal coherence to identify patterns within the data, such instability limits both accuracy and confidence in its outputs.

The Origins of Inconsistency

This unevenness has deep roots in the history of exploration practice. Each organization, and often each individual team, developed its own methods for collecting and describing geological information. Local conditions and personal preferences influenced how data was recorded and maintained. Over time, these habits solidified into self-contained systems that rarely aligned with one another.

What began as pragmatic flexibility gradually became an obstacle to integration, leaving the industry with information that must be reinterpreted before it can be compared, a process that almost always introduces new errors and noise. The widespread use of Microsoft Excel as a de facto database, common across exploration companies, further erodes data integrity through copy-paste mistakes and incorrect operations, an issue well recognized in many fields.5,6 Although systematic study of errors in exploration data is limited, inaccuracies of about 0.5–16% have been estimated for transferring geologic point data from field maps to digital format.7

Preparing Data for Machine Learning

Configuring exploration data so that analytical models can use it requires reconstruction, not simple reformatting. Many older assay results were generated with detection limits and analytical precision incomparable with current analytical methods, while equivalent rock types have often been catalogued under different names or coding conventions. Establishing a stable foundation means reconciling these records so they convey consistent meaning across time and context.

Automation has recently started to change how this work is performed. Tasks once handled manually can now be executed through algorithms that align historical records with modern databases and adjust them into a coherent form ready for modelling. However, human review remains indispensable. Geologists must ensure that automated corrections preserve geological truth rather than impose numerical order. The most dependable results emerge where computational precision and expert judgement converge, each tempering the other to maintain integrity in the final dataset.

"As data quality improves through more consistent and interoperable practices, machine learning will move beyond its role as an analytical convenience and become integral to how geological knowledge evolves."

Toward Shared Standards and Quantitative Data

Improving data quality within individual projects is only part of the solution. The broader potential of ML will materialize when information can move seamlessly across the industry, and when quantitative, objective geoscientific observations, rather than qualitative descriptions, become the standard, as demonstrated by advances in core scanning.8

At present, each company repeats the same cycle of cleaning and restructuring whenever data is exchanged or reported. Shared design principles, such as capture codes for core logging,9 along with open-source data standards, could eliminate much of this duplication, allowing information to circulate between technical teams and across regions without loss of meaning. With compatibility at this scale, anonymized datasets could be integrated to characterize mineral systems far larger than any single operation, strengthening both model training and reproducibility.

Achieving this degree of consistency depends less on new technology than on coordinated behaviour. The necessary tools are largely in place; what is missing is agreement on how they should be applied and maintained. A common approach to data structure and stewardship, like the frameworks established by the Open Geospatial Consortium,10 would give the industry a unified language for its information. As ML becomes more embedded in exploration, alignment around such practices will shift from aspiration to necessity.

The Direction of the Industry

Exploration is entering a stage where the true impact of ML will be determined by data discipline. Many teams already apply these tools to refine interpretation and test geological ideas, yet their broader value remains constrained by the quality of the information available. Meaningful progress will likely come not from new algorithms but from a more deliberate, industry-wide approach to how data is generated and maintained. Treating information management as an extension of the scientific method, instead of an administrative obligation, will shape how effectively ML systems can be used.

As data quality improves through more consistent and interoperable practices, ML will move beyond its role as an analytical convenience and become integral to how geological knowledge evolves. This shift will turn isolated analysis into cumulative understanding, where each dataset reinforces the next and discovery becomes a collective outcome of disciplined information.

If you want to understand how ML can strengthen your exploration workflow and how to prepare your data for it, our Geoscience Team is available to discuss approaches that match your project’s needs.

<hr/>

.png)

.png)

.png)